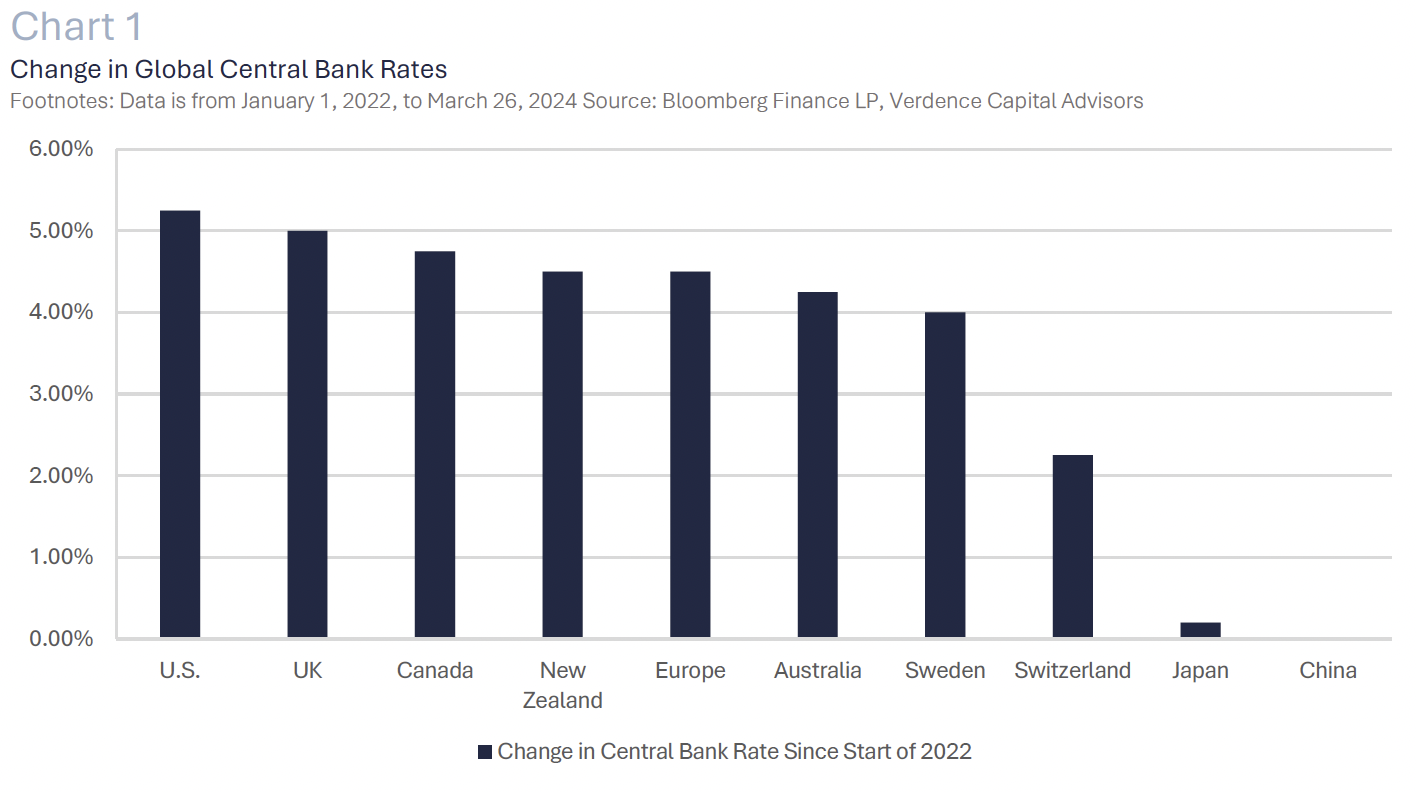

Since the start of 2022, investors have witnessed one of the most aggressive central bank tightening cycles in decades. The biggest global central banks have increased their benchmark interest rate by, on average, over 400 bps (i.e., 4.0%), with the U.S. raising rates the most (+525 bps). (Chart 1). The actions taken by these central banks have been warranted to tackle a massive inflationary cycle as we work to unwind the excess stimulus delivered to the world economy during the pandemic. Finally, on March 18, 2024, the Bank of Japan joined the other major central banks to raise interest rates for the first time in 17 years. The Bank of Japan did not just raise interest rates, they were the last central bank to end a nontraditional type of monetary policy called negative interest rate policy (a.k.a. “NIRP”) which they have had in place since 2016.

In this white paper we seek to educate our readers about what a negative interest rate policy is and why it may be used by central banks. We will discuss the reasons the Bank of Japan was finally able to abandon their negative interest rate policy. Lastly, while Japan has been the last to join the global tightening cycle, we will explain what the end of this nontraditional policy tool means for global assets.

What is Negative Interest Rate Policy, and Why Use it?

Central banks use monetary policy to support economic growth and/or maintain price stability. In times of economic weakness, central banks will cut interest rates to spur growth. In contrast, they will raise interest rates if they need to cool economic growth. From an inflation standpoint, price stability is another mandate for central banks. Central banks can raise rates to bring inflation down or cut rates if deflation (a persistent period of a decline in broad prices) or disinflation (temporary slowing in increases of inflation) threatens their long-term inflation target.

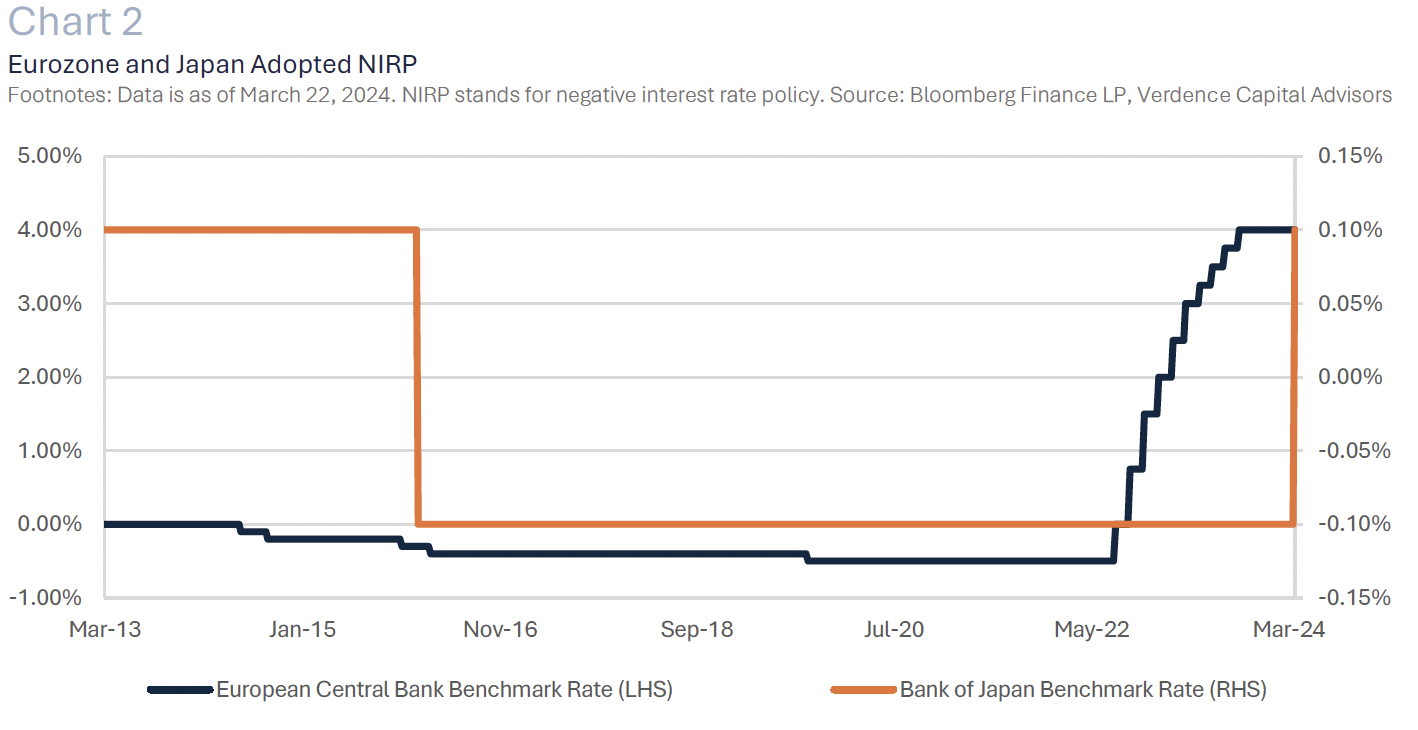

Negative interest rate policy is not a traditional monetary policy tool; it is used as a last resort. It has been used by central banks in Europe and Japan over the past decade when they exhausted all options to avoid deflation and/or spur economic growth. After the Great Financial Crisis and the Eurozone peripheral debt crisis, a persistent period of inflation growing below the European Central Bank’s target rate ensued. As a result, the European Central Bank cut rates into negative territory in 2014 and continued cutting further into negative territory through 2019. The Bank of Japan has used negative interest rate policy since 2016 as they battled a deflationary environment. (Chart 2).

When a central bank sets a negative interest rate policy, that country’s central bank charges commercial banks to hold excess cash, and those banks do not pay interest to depositors. Even though the rate is set below zero, banks have not typically passed that onto depositors by charging them. Instead, depositors earn zero interest on the cash they hold at banks. It is hoped that this negative interest rate policy will incentivize commercial banks to lend and consumers to spend instead of hoarding cash.

How the Bank of Japan was able to Abandon Negative Interest Rate Policy

The bursting of the Japanese property and stock market bubble and policy errors in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to persistent economic volatility, deep recessions, and a deflationary spiral in prices. As a result, the Bank of Japan was forced to keep interest rates at or near zero through most of the 1990s and early 2000s with a brief move higher leading up to the Great Financial Crisis. Many historians refer to this period for Japan as the “lost decade.”1 While Japan’s aging demographics, currency volatility, and emerging Asian economies can also be pinpointed as challenges to the Japanese economy, wage stagnation was a major driver of the consistent deflationary pressures.

However, Japan has finally seen stability and even solid wage growth. Wages can be a major and difficult inflationary or deflationary challenge for a central bank to tackle. Higher wages can fuel inflation while lower wages keep prices low and fuel deflation. In the country’s annual “springtime negotiations” (March 2024), the major labor union confederation (i.e., JTUC-Rengo) announced a massive increase in the average base wage rate (3.7%), and this was after last spring’s robust increase.2 Therefore, the Bank of Japan felt that higher wages warranted an end to negative interest rate policy.

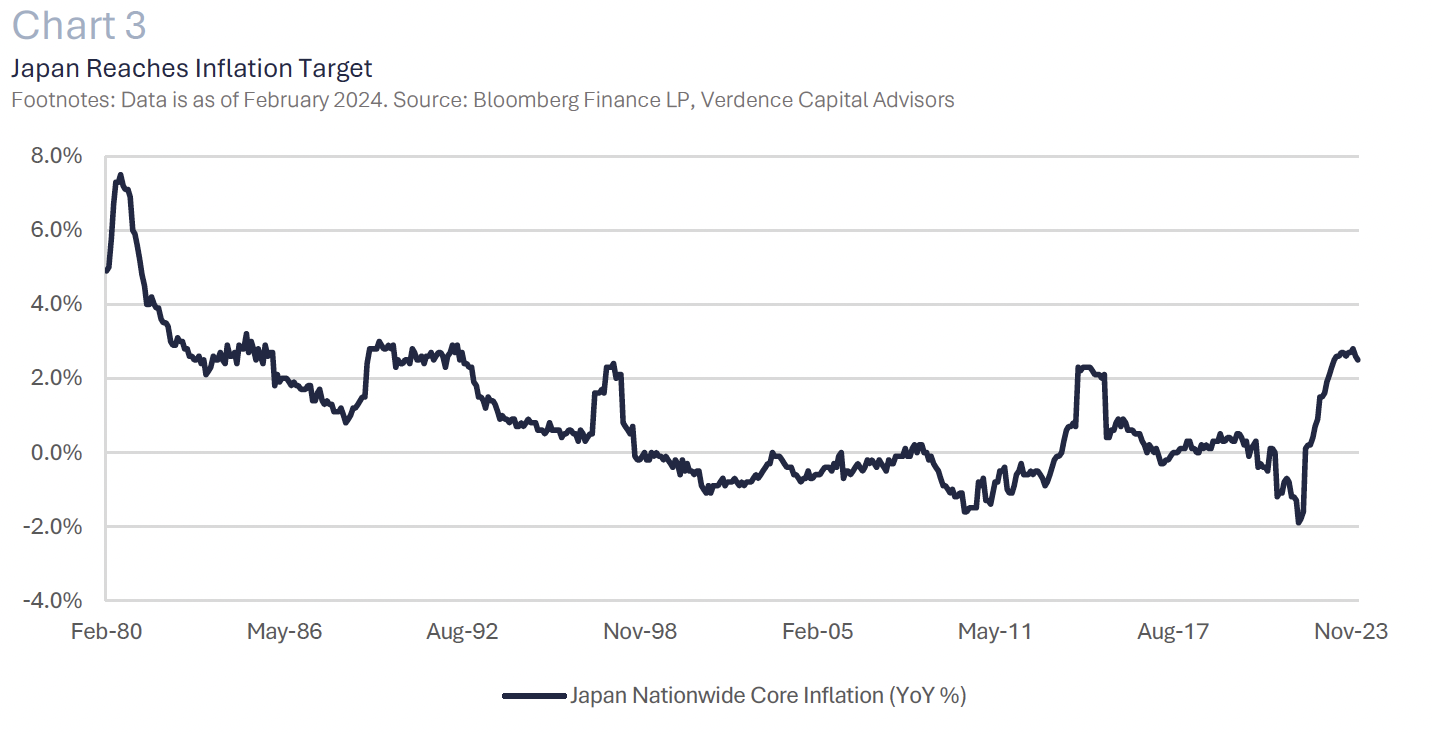

In addition, a global inflationary environment due to the aftermath of the pandemic has pushed prices higher in Japan as well. Japan’s Nationwide Consumer Price Index is growing 2.5% year over year, the highest level of inflation for the country since the early 1990s. (Chart 3). This is comfortably above the Bank of Japan’s inflation target (i.e., 2.0%) so nontraditional monetary policy was no longer needed.

What does the End of Negative Interest Rate Policy Mean for Global Assets?

The Bank of Japan’s move was not a shock to investors. However, their dovish comments after they made the announcement have muted the impact on global stocks and bonds. The Bank of Japan reiterated that they would keep an accommodative monetary policy stance and are willing to reverse course if progress on wages and inflation stalls. Therefore, it has been more of a symbolic event than a market moving event.

However, investors should be prepared that zero or negative interest rate policy is likely a thing of the past. While most central banks are gearing up to cut rates this year, we do not expect them to be able to use this nontraditional tool again unless a major economic calamity occurs. Global inflation remains a major risk, and what central banks have learned from past mistakes is that a stop-and-go monetary policy has not worked for economic growth or price stability.

For bondholders, we are settling into a new interest rate regime where peaks and lows in rates throughout economic cycles may be higher than we are accustomed to. We have seen this impact through the amount of negative-yielding debt around the world falling from over $18 trillion to less than $500 billion. (Chart 4). The long-term impact on bond investors depends on whether the Bank of Japan has more rate hikes ahead. However, what is clear is that the path forward for rates in Japan is likely higher, but the timing and magnitude are less clear. This may impact U.S. Treasuries in the long run. Japan has been one of the top three largest holders of U.S. Treasuries as negative interest rates have driven flows out of Japanese bonds to higher-yielding countries. If a Japanese investor can earn a positive yield in their own country and not have to withstand currency volatility, flows to U.S. Treasuries may moderate. This is concerning at a time when the U.S. Treasury is forecast to increase the amount of U.S. Treasury debt by ~30% in the next five years.3

For Japanese equity investors, the impact should vary across sectors over the long run. Major commercial banks should benefit as margins increase with higher interest rates. Insurers should benefit as long-term rates increase. Energy-intensive sectors may benefit if the Yen appreciates and the cost of energy resources moderates. We expect some of the losers to Japan’s move to be real estate and homeowners as nearly three quarters of the home loans in Japan are floating rate.4 In addition, the hospitality sector may lag if the Yen appreciates and hampers tourism. Lastly, while regional banks may benefit from higher margins, we are concerned about rising defaults in “zombie companies” that were able to stay afloat due to record-low interest rates. These are referred to as “zombie companies” as they cannot keep up with debt payments with their profits alone. According to Bloomberg, one in six Japanese companies are considered “zombie banks.”5

Our View

At this point, the move by the Bank of Japan has had little impact on the global markets. This is likely because it was not a shock to the system but more of a symbolic signal. The Bank of Japan was the last standing symbol of negative interest rate policy. While the positive and negative long-term ramifications of negative interest rate policy are still being studied, we believe normalization in interest rate policy is healthier for the long run than manipulating monetary policy. The Bank of Japan being able to bring rates into positive territory reminds us that we are still working out the consequences of the pandemic, but higher highs and higher lows in interest rates are something we should get accustomed to for the long run. We are closely monitoring our exposure to Japanese equities, especially at the sector level. In addition, this confirms our cautious outlook on long-term bonds, especially in the U.S.

If you have any questions or comments, please reach out to your financial advisor.

Megan Horneman | Chief Investment Officer Past performance is not indicative of future returns

- https://internationalbanker.com/history-of-financial-crises/japans-lost-decade-1992/

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/03/japan-ends-negative-interest-rates-economy-monetary-policy/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/

- https://finimize.com/content/the-winners-and-losers-as-interest-rates-finally-rise-in-japan

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-19/japan-s-zombie-firms-on-rise-as-boj-paves-way-for-rate-hike