In the years leading up to the COVID pandemic, many economists and academics estimated that China’s economy would replace the U.S. as the largest global economy by as early as 2030. China’s soaring property market, rising middle class, technological advancements and its spot as the leading global exporter would be enough to overtake the U.S. However, in recent months we are witnessing a rapid deterioration in not only economic growth, but the Chinese currency, consumer and investor confidence and the hopes that China can take over the U.S. by the end of the decade.

We realize we cannot cover all the complexities of the Chinese economy in one white paper so here we will focus on a brief history of China’s rise to be a global superpower, the recent obstacles that can be drawn back to the policies implemented over past decades and whether this may be buying opportunity for Chinese equities.

China: From an Emerging Economy to a Global Superpower

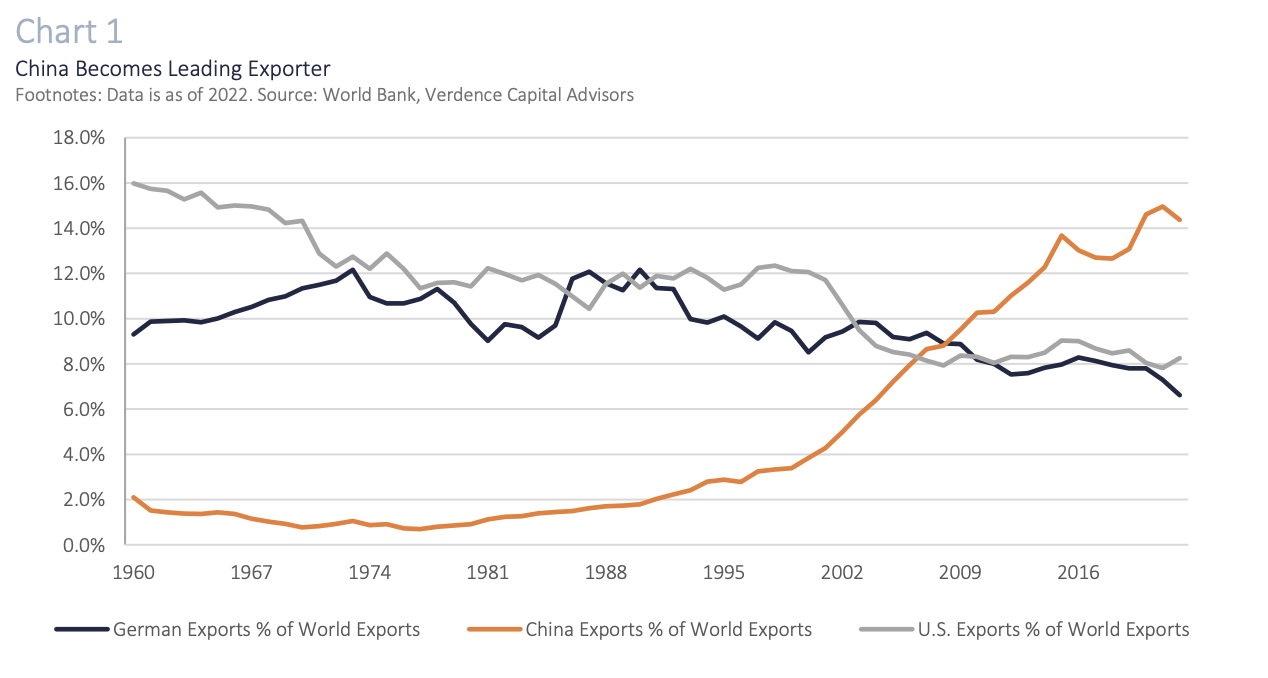

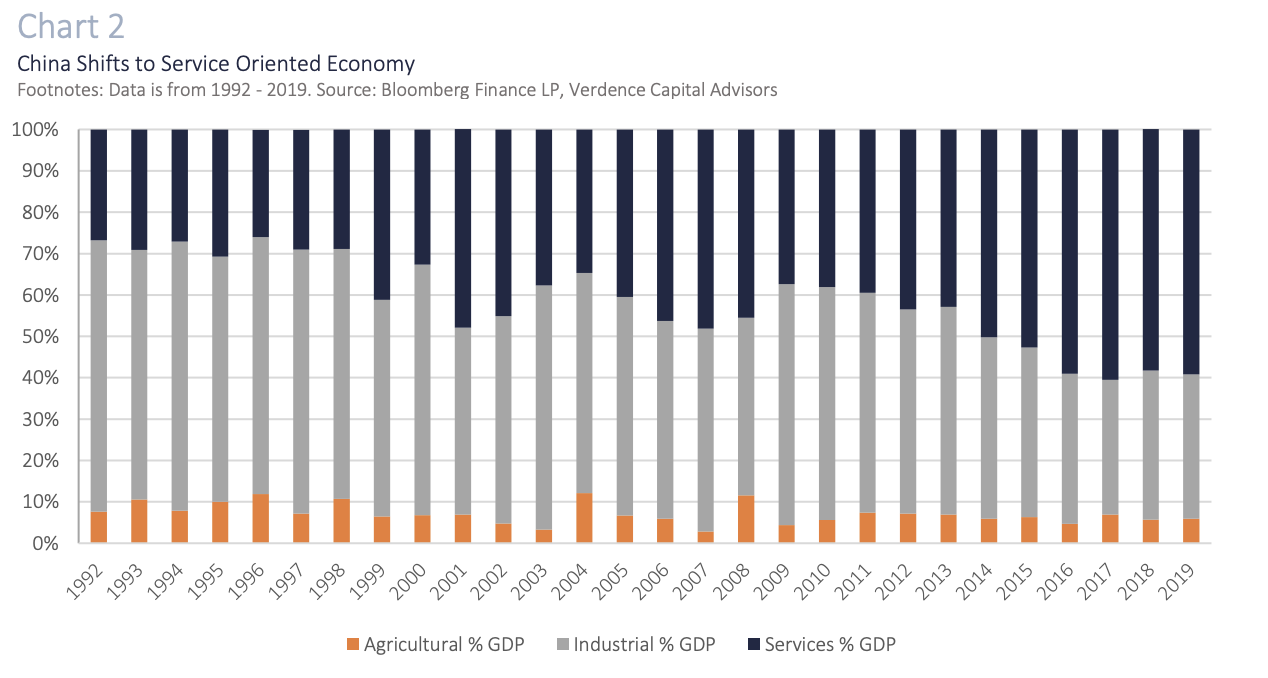

The transformation of China into a global superpower has been swift but not always smooth. China has faced many obstacles with periods of economic stagnation, civil unrest, and geopolitical turmoil. However, by the 1980s, Chinese leadership was focused on reforms, lifting the incomes of the lower and middle class, and attracting foreign capital through tax incentives.1 By the 1990s, China was experiencing a plethora of capital inflows from international investors and from companies that wanted to take advantage of low labor costs and connect themselves with international trade. As a result, in 2009, China became the world’s largest exporting country, surpassing both the U.S. and Germany. (Chart 1). There was also a push to shift their economy from a rural agricultural base to a more urbanized service-oriented country. In fact, the service sector made up ~30% of their economy in 2000 and in the year before the pandemic (2019) it made up ~60% of the economy. (Chart 2). As citizens shifted to urban areas, a property boom began in the early 2000s. To further incentivize people to move, the government shifted from state-owned real estate to private homeownership. They encouraged banks to provide attractive lending rates to hopeful homeowners and construction companies began buying up land at a rapid pace. Then came the global financial crisis in 2007-2009. Governments around the world implemented massive stimulus packages and the Chinese government concentrated their stimulus on more housing, infrastructure, and transportation. This helped China avert the worst of the global downturn. However, the fiscal actions instigated careless property management and lending practices, pushed housing prices higher, fueling speculative buying and ultimately creating an inflationary environment. The only solution for the Chinese Government has been to try to cool the property bubble.

China’s Structural Challenges

Despite China’s size, population, and far-reaching Government power, they are not immune to booms and busts like all economies. To slow the overheating property market and bring inflation down, the Government has been forced to implement restrictive policies on speculators (e.g., higher down payments and taxes on multiple homes). However, housing is just one of the many challenges plaguing the economy at this point. Below is a list of the main factors affecting growth for the world’s second largest economy.

- Property bubble bursting: The Chinese real estate bubble is bursting. According to data from the China Real Estate Information Corporation, new home sales by the top 100 developers dropped 33% in July compared to a year earlier.2 Home prices are broadly falling and the decline in real estate is exposing bigger problems. Most property developers relied heavily on debt and turned to the shadow banking system for funding. The shadow banking system exploded after the Great Financial Crisis as property developers needed funding outside of traditional Chinese banks due to regulatory limitations, limited supply of credit and the Chinese Government’s control over interest rates.3 The shadow banking companies and securities firms. These products are typically linked to the value of real estate. However, with the property market deteriorating, developers are walking away from projects (some of which they have taken money from homeowners) and bankruptcies have been piling up. With some well-known developers filing for bankruptcy or missing debt payments (e.g., Evergrande, Country Garden) the focus is turning to the exposure in the shadow banking system with some also recently missing payments to investors (e.g., Zhrongrong Intl. Trust).

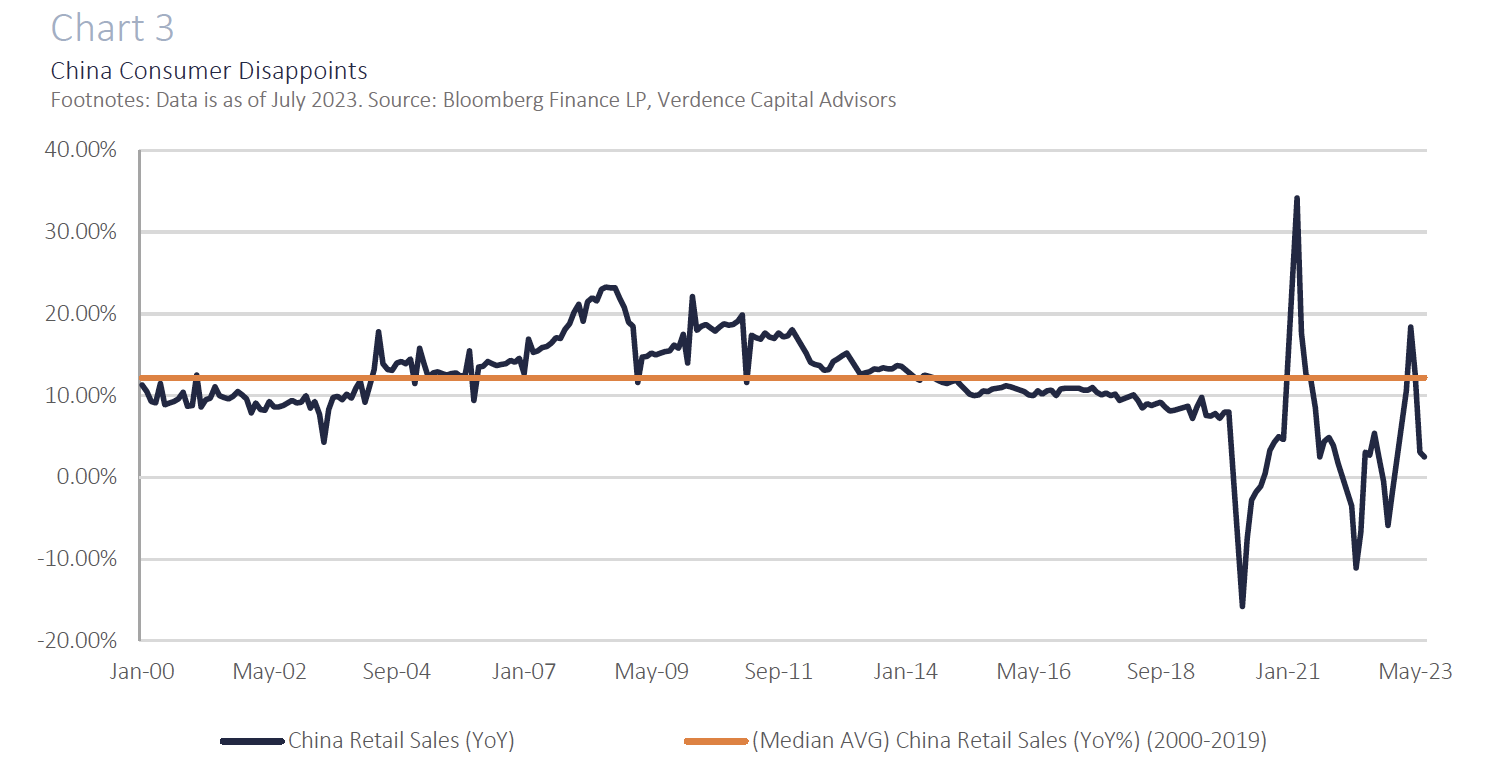

- Consumer Slowdown: The Chinese government has depended on consumer spending to cushion the blow from the deteriorating housing market. However, many Chinese citizens have also invested heavily in real estate as an investment and are now squeezed. The pent-up demand spending after the long-awaited reopening of China due to COVID has been disappointing. Retail sales jumped nearly 20% (YoY) earlier this year and are now growing 2.5% (YoY), well below the pre-pandemic spending trend (average ~12% YoY growth in sales). (Chart 3).

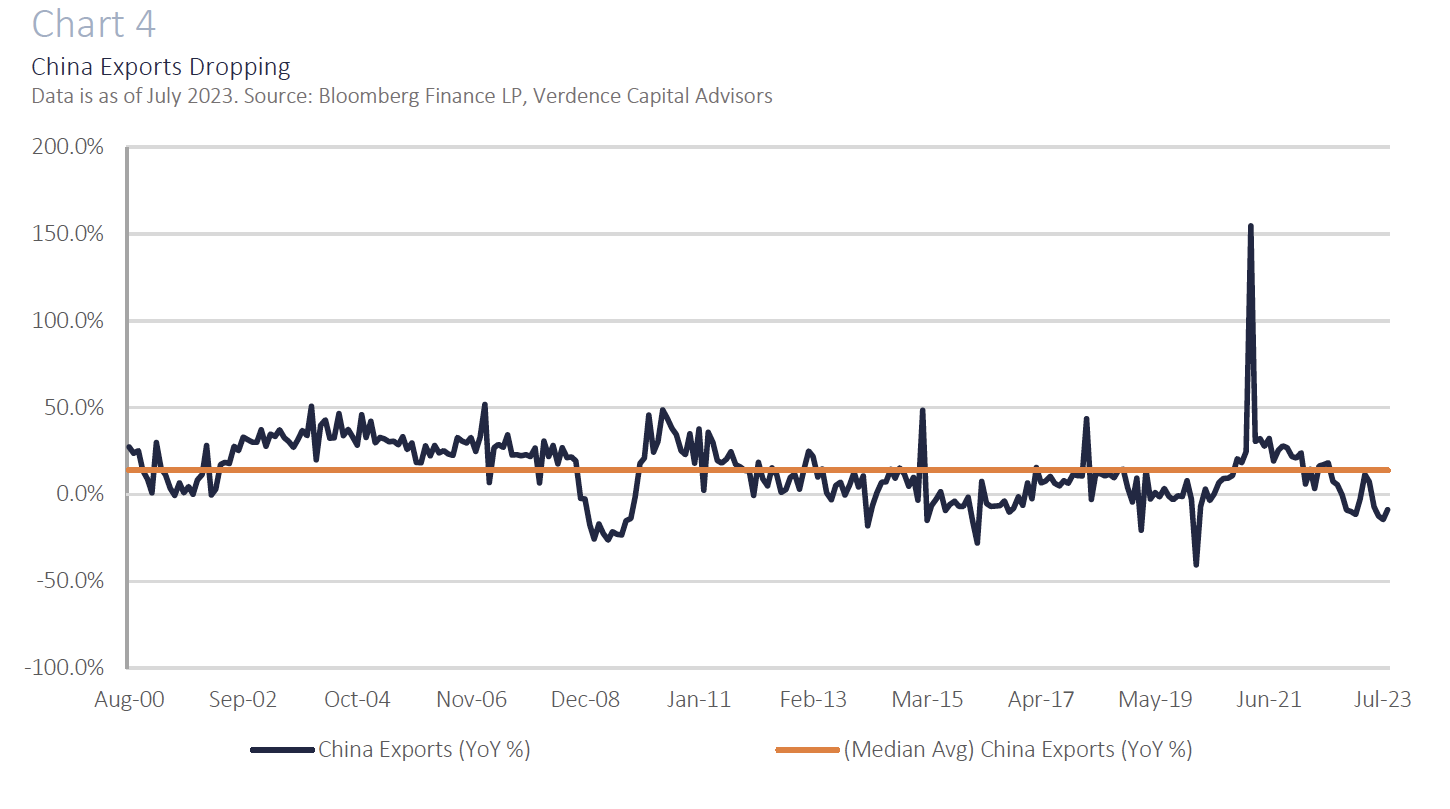

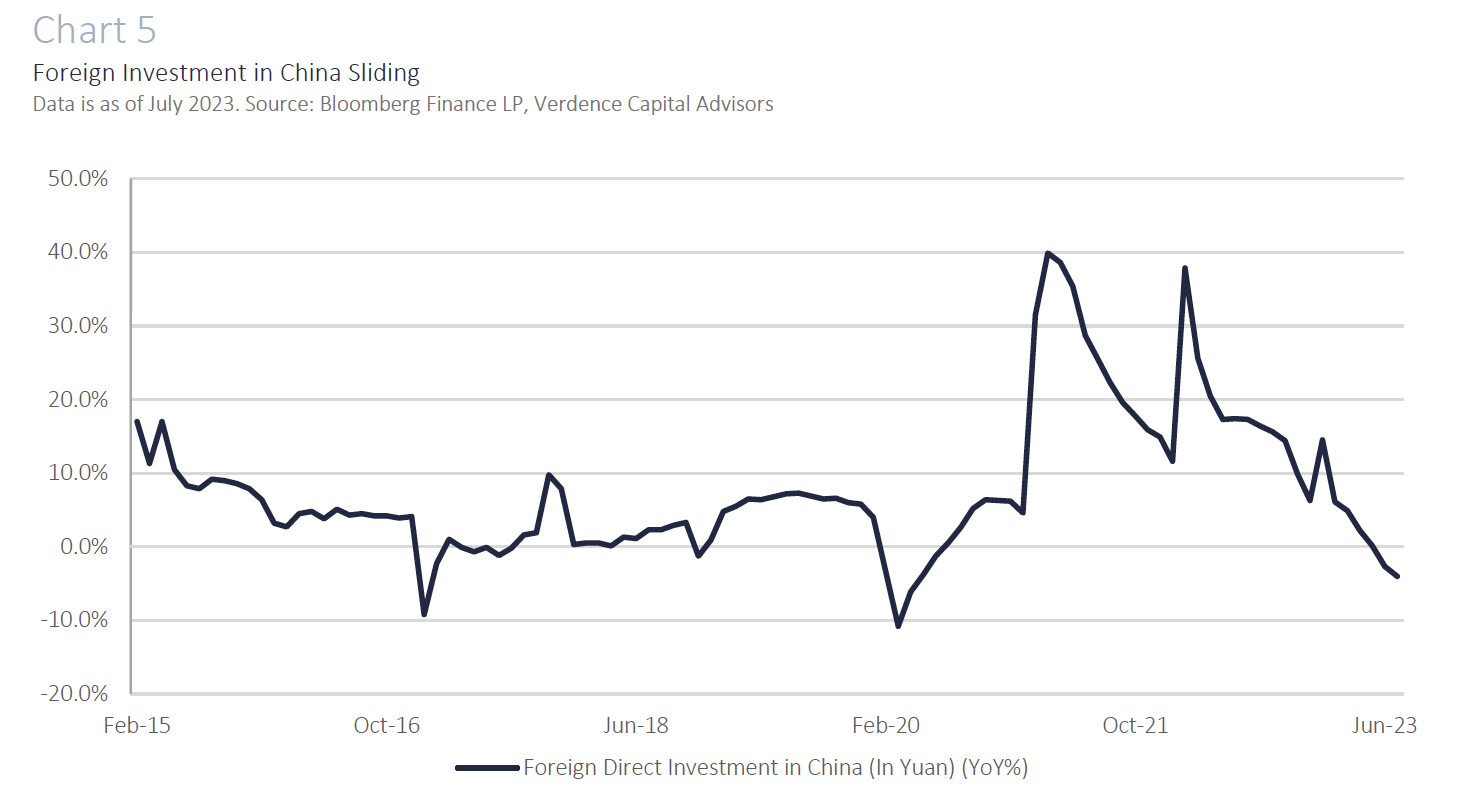

- No longer an export behemoth: Chinese exports declined for the fourth consecutive month in August and fell for the ninth month out of the past 11. (Chart 4). This is partially due to slowing global demand but also due to companies diversifying their manufacturing needs after lessons from the pandemic (e.g., supply chain disruptions, rolling lockdowns). In addition, rising labor costs, the U.S./China trade war, domestic political controls, and geopolitical risks are deterring companies from relying too much on China for production. As a result, foreign direct investment has plummeted. (Chart 5). A recent survey by the European Chamber of Commerce in China “noted that one quarter of its members currently operating in China were considering closing and moving their operations elsewhere.”4 In addition, some major U.S. tech companies are shifting some of their production to other countries (e.g., Apple, Google).

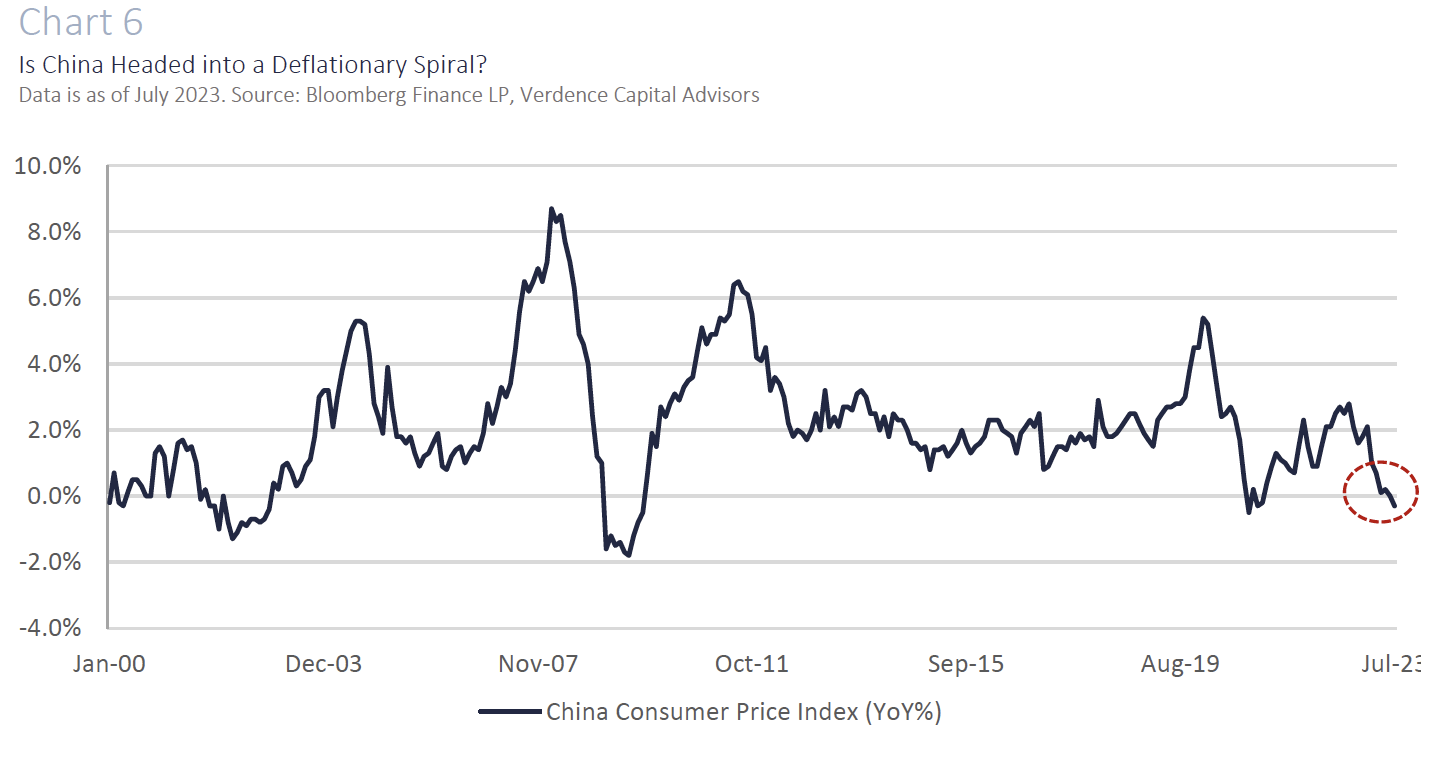

- Deflation risks: The deterioration in home prices, deleveraging in the property market, slowing consumer spending, and the weakest economic growth in decades are also resulting in deflation fears. China’s Consumer Price Index dipped negative on a year-over-year basis in July, the first negative reading since the pandemic (Chart 6). While one-off factors (e.g., commodities) have been blamed for the decline in July, current estimates show inflation to be very tepid in the coming quarters.

- Currency decline: As investors pull money from China, the economy weakens and interest rate differentials remain wide between the U.S. and China, the Chinese Yuan has declined to a 16-year low versus the U.S. dollar. This is concerning if China is deliberately opting to keep the currency weak to boost exports. This has been a constant cause of tension between China and many global Governments as China goods look cheaper compared to their global counterparts. It could also result in speculation/mistrust that China is looking to change its policy to keep the Yuan stable (China allows an up or down movement of Yuan of 2% per day).

- Local debt a challenge: The loss of revenue from real estate, slowing economy and lingering damage from COVID lockdowns has resulted in soaring local debt also known as LGFVs (Local Government Finance Vehicles) (76% of GDP). The growth in LGFVs is a threat to China’s economic growth especially if there are widespread defaults that force the Chinese Government to intervene.

- Demographics worsening: In 2022, the Chinese population declined for the first time since the 1960’s. The “one child” policy introduced in the 1980s is showing its negative ramifications. The fertility rate has declined from 7.5 births per woman in the 1960s to ~1.0 births per woman now. However, it is not just past policies, the Chinese population are having less children. This is trouble for many areas of the economy including the property market. According to the United Nations the portion of the population relied upon to clear up real estate excesses (25-39) is expected to fall more rapidly over the next 10 years.5 Declining demographics is also a concern for social programs and retirement systems. For example, according to the Brookings Institute, China’s working age population peaked in 2011 at 900 million and will decline to ~700 million by mid-century. Those 700 million will need to support the estimated 500 million Chinese citizens over the age of 60 (compared to 200 million over 60 currently).6

- Young employment concerning: After the youth unemployment rate hit 21.3% in June, the National Bureau of Statistics in China announced it will stop releasing data. Rising youth unemployment has been driven by education disruption and limited job prospects for the younger population due to COVID lockdowns. In addition, there are skill mismatches as young workers often are employed in the services industry, which is still struggling from COVID related weakness.7 Lastly, the slowdown in economic growth has led companies to be hesitant to add employees, especially young employees who require training.

Despite China’s size, population, and far-reaching Government power, they are not immune to booms and busts like all economies.

Is China a Buying Opportunity?

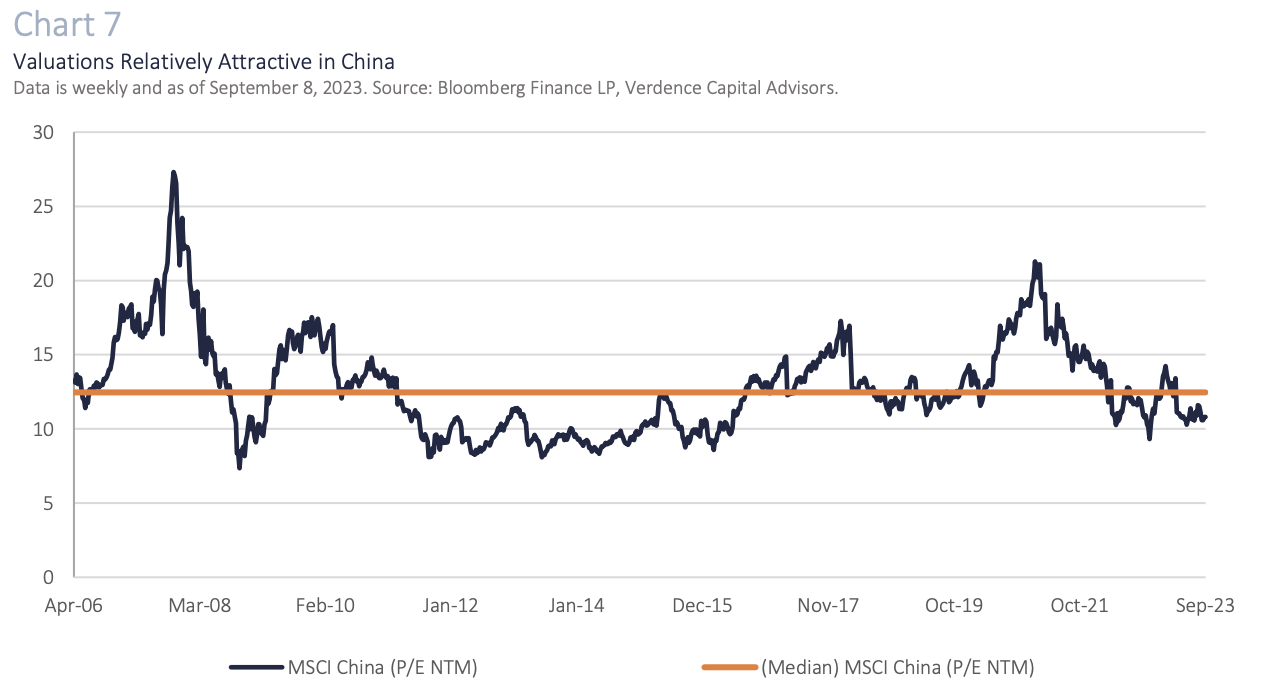

Chinese equities are lagging the rest of the world this year because of their many challenges. The MSCI China Index is underperforming the broad MSCI EM Index by over 900 bps and underperforming the MSCI AC World Index by over 1800 bps.8 As a result, valuations when looking at the forward price to earnings multiple are at a discount to their historical average. (Chart 7). Emerging market equities are an important part of a well-diversified portfolio and China is a major portion of the MSCI EM Index (~30% of the Index). Therefore, it is difficult to completely ignore Chinese equities in a well-diversified portfolio. However, we are cautious about the asset class and recommend a neutral to slight underweight allocation for more conservative investors. Active management is crucial in the space as good managers can pick companies that are less dependent on the domestic Chinese economy and more multinational and may be better equipped to navigate the challenging political climate.

The “one child” policy introduced in the 1980s is showing its negative ramifications.

Our View

China is facing significant economic and political challenges. Some have to do with their responses to the COVID pandemic, but it does not stop there. The bill for years of over investment and leverage is finally coming due. Thus far, China has announced targeted stimulus measures (e.g., lowering rates, increasing market liquidity, easing property buying restrictions), but we have not seen the “bazooka” of stimulus. As a result, Chinese citizens and global investors have not responded as well as the Government would like to see. In addition, the scars from the Russia/Ukraine war and China’s ongoing aggression in the South China Sea make international investors nervous about investing in the country. The rest of the world is not immune if there is a prolonged slowdown in the Chinese economy. On the positive side, disinflation or deflation in China can help the developed nations that are dealing with elevated inflation. On the negative side, the emerging Chinese consumer has been a theme that has helped other export driven nations and will be a headwind if their willingness to spend remains tepid. In addition, the lack of transparency and uncertainty from a political standpoint is a concern that can further damage global partnerships. We will continue to monitor the Chinese Government’s response and weigh the ongoing risk with the reward if a buying opportunity arises.

If you have any questions or comments, please reach out to your financial advisor.

Megan Horneman | Chief Investment Officer | [email protected] Past performance is not indicative of future returns

2 https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/01/economy/china-real-estate-country-garden-intl-hnk/index.html

3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shadow_banking_in_China

5 https://www.abrdn.com/docs?documentId=GB-131022-182105-1

6 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-shrinking-population-and-constraints-on-its-future-power/

Data is as of September 7, 2023.